In which Burnsy returns to Central Library so Librarian Matt can show him how he can make all of his Christmas presents this year. He has such a lucky family.

What Is Hull’s Unluckiest Address?

A tale of marine misfortune from our cub reporter Angus Young.

Widely regarded as being one of the world’s most dangerous jobs, it’s little wonder that superstition was rife in Hull’s deep-sea fishing community. From wives refusing to wave farewell to trawlers leaving St Andrew’s Dock to fishermen who avoided the colour of green at all costs, lucky omens good or bad were passed down through the generations. Even seemingly innocuous acts such as sneezing could carry a message. Turning your head to the left while sneezing was regarded by some as back luck on the next trip. In some homes, wives would even burn new brooms to produce a favourable breeze to bring their loved ones home safely.

Hull author and historian Alec Gill charts many of these tales in his book Superstition: Folk Magic in Hull’s Fishing Community but one can only wonder what Hessle Roaders made of Hull’s unluckiest address back then.

Today Liverpool Street is occupied by industrial units but during the heyday of the fishing industry it was lined with terraced housing and was just a short walk away from the dock itself. Even with all that had been written about the loss of life at sea during those years, it’s still difficult to comprehend a series of human losses experienced by those living at Number 24. For in the space of just 39 years, five men who called the house their home died in separate tragedies at sea.

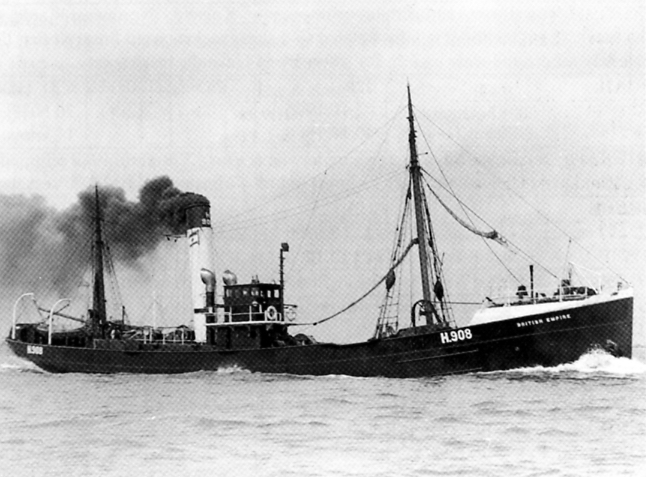

The toll began in 1911 when 23-year-old George Smith was drowned during a trip to the Barents Sea on the steam trawler British Empire. A newspaper report on his death said: “Smith, who was a spare hand, was helping to shoot the gear when his foot was caught in the bight of the quarter rope and he was pulled overboard. The unfortunate man was hauled out of the sea in the trawl but was dead. The body was taken ashore subsequently on the Norwegian coast and reverently buried, a crowd of people living in the district attending the funeral.”

Four years later George’s elder brother Frederick, 30, was lost on another steam trawler, the Commander Boyle. Out on only its second fishing trip, it was sunk by a mine. Two other crew members died in the incident.

The next tragedy struck the family in 1925 when mate Daniel Smith was lost with the rest of the 14-man crew of the steam trawler Axinite. She was last heard of fishing off the Icelandic coast. Back at 24 Liverpool Street, his mother was now mourning another son lost at sea. “My son Daniel has spent all his working life at sea. I’m afraid I have little hope of good news now,” she said. Remarkably, the three deaths followed the earlier loss of a fourth son when the family lived elsewhere in Hull.

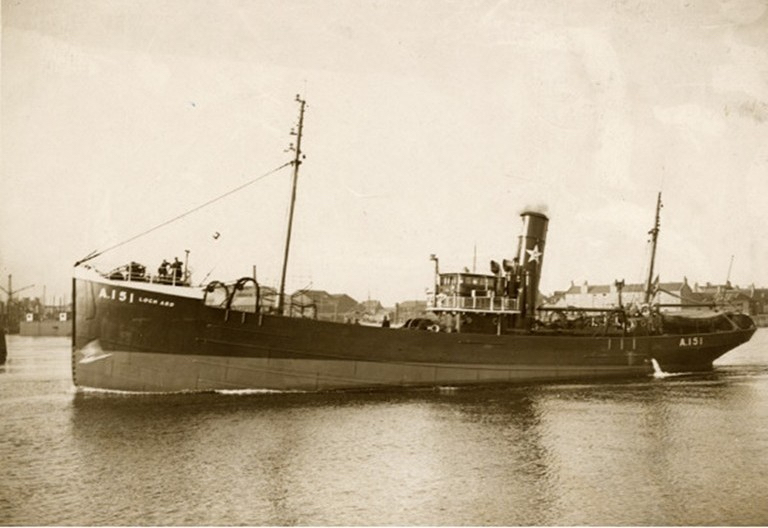

By 1934 the Shears family were living at Number 24 when the Hull trawler Loch Ard was lost with all hands while fishing off Iceland. Skipper Bill Shears had been at the helm. Seven members of the crew had been married and the trawler’s loss left 22 children fatherless. Skipper Shears’ widow Beatrice continued living at the house and she later re-married but fate would soon leave her mourning once again. In 1940 her new fisherman husband John Thompson was killed when the Aberdeen-based trawler Sansonnet was sunk by enemy aircraft off the Shetland Islands with the loss of all hands.

The sad chain of events connected to Number 24 has been pieced together by Jerry Thompson, chairman of the Hull Bullnose Heritage Group which runs the Hull Fishing Heritage Centre in Hessle Road. A former trawlerman himself, his mother’s father was also lost on the Loch Ard. Jerry said: “This all came about when I put the lost trawlemens’ surnames into the streets they were lost from to create a new database. It took me about two years and I am still finding new lost trawlermen in our research who are not on the original city lists. My mother’s father was lost in 1934 on the Loch Ard when she was 13-years-old. As a young lad, she would always talk to me about her father.”

Overall, an estimated 6,000 trawlermen who sailed from Hull lost their lives at sea.

What Is My Favourite Building In Hull? Dean Wilson

What Are Your Top 5 British Noir Novels? Nick Triplow

How Old Is Big Ben?

CuriosityCast Ep.07 An Audience With Jacko – Part 1

He doesn’t like to be called a legend but we’re going to do it anyway, the indomitable Paul Jackson – the man who brought Hull the Adelphi Club – is our guest for a two-part CuriosityCast. The chat is everything from serious to funny to righteous to touching as Jacko invites Burnsy into his home to discuss his long life in music and much more.

What Is My Favourite View In Hull? Chris Speck

How Did Hull Fair End Up On Walton Street?

Hull Fair has been going for over seven centuries but only moved to Walton Street a mere 136 years ago. Our cub reporter Angus Young finds out why.

On your annual trip to Hull Fair, have you ever wondered how it got to Walton Street in the first place? The answer partly involves a foul-smelling drain, a railway company and the thwarted ambitions of a Victorian developer.

Well before the fair moved to the site in 1888, the western side of Walton Street was already one of Hull’s new working-class neighbourhoods. The man responsible for most of it was James Beeton, the owner of a successful basket and furniture manufacturing company in High Street who, by the late 1850s, was also a significant landowner. Two of his landholdings lay either side of the River Hull, off Holderness Road and Anlaby Road. Both were initially used to grow willow to supply his business with raw materials but as Hull’s population began to boom, Beeton spotted an opportunity and turned them for new housing.

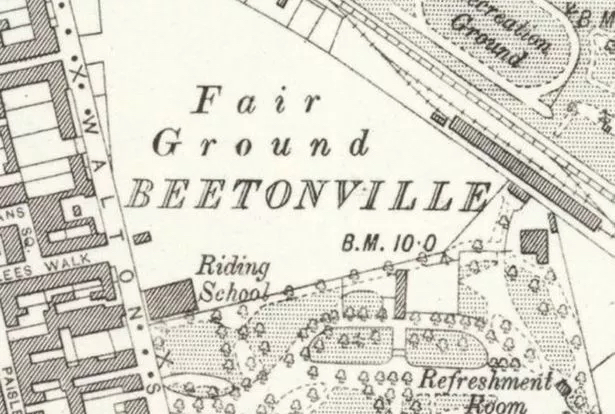

As a leading figure in the Hull, Beverley and East Riding Freehold Land Society, he also wielded a degree of political power as membership of society secured legal voting rights in elections. Beeton named a street after himself in his new Somer’s Town estate in East Hull but went a step further in West Hull by naming the new neighbourhood Beetonville.

Most of Beetonville’s housing, shops and pubs to the west of Walton Street started to take shape in the 1860s, forming a network of terraces reaching Albert Avenue which was laid out from 1874. It even had its own church. Until then, Walton Street had been little more than a country lane between Anlaby Road and the ancient Derringham Bank, what is now known as Spring Bank West.

The lane marked Hull’s old municipal and parliamentary boundary and was bordered by fields and a few farms but Beeton’s new housing changed all that. However, not everyone was pleased with the results. Crowded living conditions and poor drainage led one critic to describe Beetonsville as “a perfect quagmire and a dismal swamp” while an alderman viewed it as a “paradise for frogs”. The problem centred on an old open drain running parallel along the eastern side of Walton Street.

Originally constructed to drain surrounding agricultural land, it soon became an outlet for human effluent from the housing across the road which eventually flowed into a series of ponds created to extract clay to be used for bricks for the new homes. Together with its surviving pig and dairy farms, Beetonville quickly became infamous for its toxic cesspools but they didn’t deter Beeton himself from living there, first in a house called Willow Glen off Walton Street and later in his own grandly-titled Beetonville Hall just off Albert Avenue where a surviving original boundary wall can still be seen today.

The presence of the drain perhaps partly explains why Beeton did not attempt to buy the land on the eastern side of Walton Street to build more houses. However, two other factors were also at play.

Opened in 1846, the Hull to Bridlington railway line formed a boundary to the land in question. Overall, the North Eastern Railway Company owned around 50 acres, which included a sidings yard. Whether Beeton attempted to buy the railway land is not known but it would have been a logical move for a confident house-building developer even with the problematic presence of the open drain. The land’s future was certainly a talking point at the time as the idea of a new recreation ground and public park was aired for the first time in a newspaper article when his vision for Beetonville was already becoming a reality.

As it turned out, ownership of the land finally changed hands in 1878 when Hull Corporation agreed to buy it from the railway company. Beeton had died six years earlier, perhaps frustrated at not being able to expand Beetonville eastwards.

We know little of Beeton’s relations with the Corporation but, as a key figure in the Freehold Land Society, it’s more than likely they did not see eye-to-eye on development issues. Whereas building Beetonville made him a rich man, the Corporation’s vision for the open space across the road was very different.

In 1885 the new 32-acre West Park was officially opened with the remaining land to the north set aside for fairs and visiting shows. Three years later, Hull Fair moved there from its previous home at Corporation Field off Park Street and has been held at Walton Street ever since.

As for Beetonville, nearly all of it was demolished and replaced with council housing in the early 1980s. Only two small terraces and the church’s vicarage remain along with a couple of faded street names on gable ends of buildings on Anlaby Road marking entry points to a largely forgotten neighbourhood.