The city apparently lags well behind in the history of painting. Until one man took up the brush, reports our maritime arts correspondent Angus Young.

When it came to applying paint to canvas, Hull was comparatively slow off the mark. The Renaissance period between the early 14th century and the mid-16th century is typically described as the artistic and cultural rebirth of Europe. Painting, sculpture and the decorative arts all flourished across the continent. However, as former Ferens Art Gallery curator Victor Galloway once memorably observed, Britain – and Hull in particular – were late to the party.

Writing in a programme for a 1951 exhibition at the gallery organised as part of the Festival of Britain, Galloway noted: “Whereas art had earlier attended divine worship, embellishment and edification, it was now an end to itself, and where formerly life was too solemn a thing to be devoted to pleasure, no other preoccupation later restrained the artist from an obsession with nature which would afford that intimacy necessary to find beauty and satisfaction in the natural order, and make it the object of one’s veneration and the motive of life’s labours.

“Britain, always on the fringe of cultural progression from the centre of things, was slow to adopt this art for art’s sake. It was, in fact, nearly a couple of centuries, in spite of royal patronage of foreigners, before this new religion had permeated the people and begun to take effect at the end of the 17th century.”

Even then, the idea of picking up a brush and making a living from art was slow to take off in Hull. When it finally did, the town’s maritime setting would be key. Galloway suggested Hull’s historical role as an isolated but important trading port initially held back the development of homegrown artists but eventually provided the inspiration behind an almost unique local school of marine painters who turned their talent to the sea rather than landscape painting.

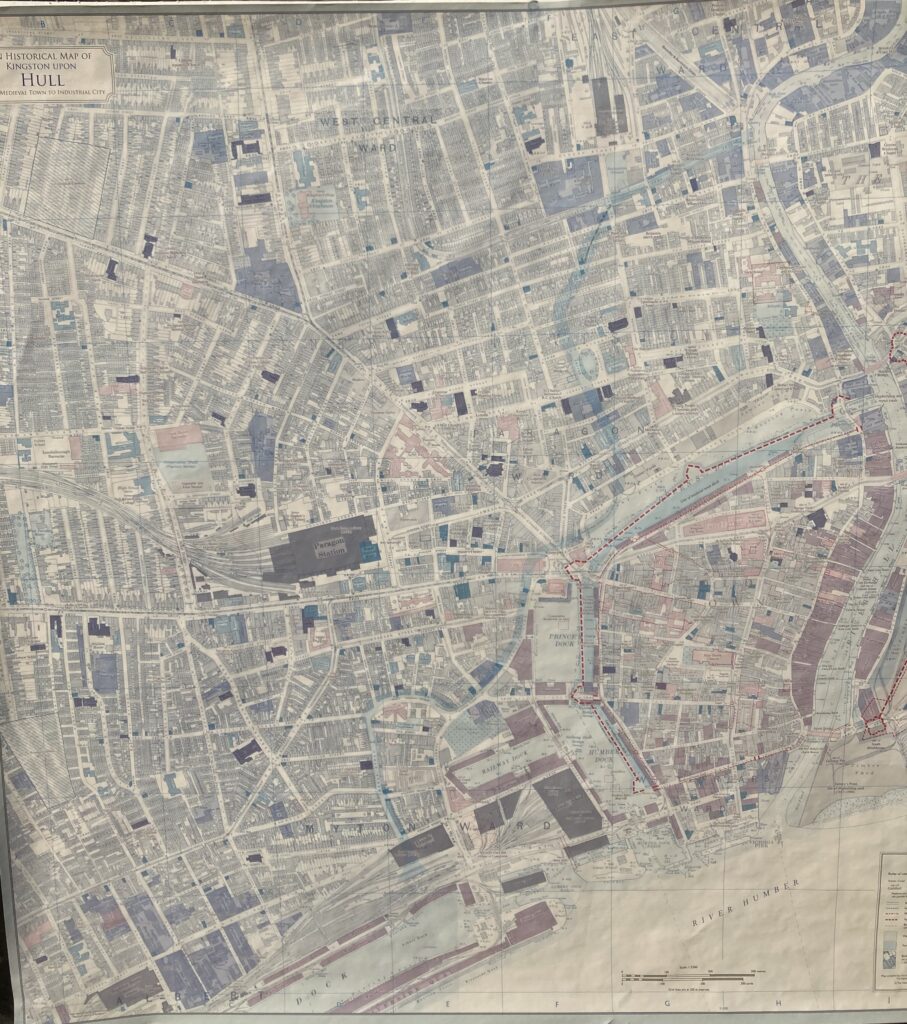

“Hull steered a course always out of step with common trends and strangely independent in politics, religion and even loyalty,” he wrote “In a place so important and individualistic, and prosperous as it always was – the home to some of the wealthiest and influential in the land – and pleasant and impressive as it certainly must have been, strange to say Hull produced practically no-one of national renown and no picture of it is known to exist that could be called important. There is, in fact, almost a total absence of local views of any class earlier than the 19th century. All we know of its appearance is derived from maps, of which there is an abundance. Hull has been well served by historians and cartographers, but few places of its size owe less to art.”

The earliest surviving marine artworks completed in Hull are a couple of paintings on panels by Martin Beckman, a Swedish engineer came here in 1681 to oversee construction work at the town’s military defences. However, it wasn’t until just over a century later that Hull’s first homegrown artist who would eventually be regarded as nationally important was born. Even then, it took another century for John Ward’s fame beyond his home town only spread after his death from cholera in 1849.

The son of a master mariner, Ward served an apprenticeship with a house and ship painter before setting up a business in High Street in the same trade. The young artist and draughtsman exhibited his first original work in Hull in 1829. Four years later he painted the large whaling picture Swan and Isabella which now hangs in Trinity House.

Another Ward painting now in the Hull Museums’ collection called Hull Whalers in the Arctic suggests he made at least two trips to the frozen whaling grounds, capturing what he witnessed on canvas while there. As such, he was one of the first British artists to actually see and paint an iceberg.

Ward was almost certainly prolific but a full catalogue of all his works doesn’t exist as many of his paintings were neither dated or signed while most changed hands on a frequent basis once they had been sold. The fact that he was little known to the arts world outside of Hull before his early death at the age of just 51 meant there was no national interest in his passing or his pivotal role as the founding father of the so-called Hull school of marine artists.

In fact, it wasn’t until Victor Galloway curated the Ferens’ exhibition of early marine paintings in 1951 that Ward and his local contemporaries and successors in Hull received any significant national attention at all. “Ward was the only truly local marine artist of any great importance, who painted much, and who can be regarded as of professional calibre and warranting national recognition,” he wrote at the time. “That such recognition has not already been accorded to him is a matter of surprise in consideration of the widespread demand for his work while he lived. He was forgotten completely and his name is only beginning to be known outside his home town.”

Today Ward’s paintings feature in the Ferens Art Gallery, the Hull Maritime Museum, Trinity House in Hull and the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC.